Uneven Democracy

Based on how the American government was designed, not all votes are created equal...

Americans pride themselves on their democracy, on the idea that everyone has an equal voice in our government, and to be honest, I’m pretty proud of it too (less so in recent years). But if anyone tells you that every citizen truly has an equal voice in our system, they possess one of two things: 1. a misunderstanding of how our government is designed and operated, or 2. a loose definition of the term “equal”. In an ideal scenario, each person’s voice would be equally valued and political representation on a macroscopic level would be proportional to the views of the American public. As a simple example, a group of 1800 Democrats and 1200 Republicans could be represented by 9 Democrats and 6 Republicans, giving each voter a representative power of 1/200 or 0.005. But let’s say that a neighboring group of 900 Republicans and 600 Democrats was represented by 9 Republicans and 6 Democrats. Locally, this is proportional and fair, but macroscopically, we now have equal representation (15-15) for unequal populations (2400-2100) because the second group has twice the representative power (1/100 or 0.01).

This may seem like an unrealistic example, but this is basically how the United States Senate has operated since 1789 thanks to the Connecticut Compromise. Gerrymandering has led to similar (but less extreme) situations in the House of Representatives. To illustrate this, we can calculate the representative power of each state or congressional district by dividing the number of representatives/senators they have by the number of voters who participated. Just to clarify units, we will define a 1 representative to 1 voter ratio as a “rep” which would make 1 representative to 1,000,000 voters a “microrep” or μrep. Furthermore, since there are 435 representatives in the House and 100 in the Senate, we will define “Total Power” as 4.35*(Senate Power) + (House Power). The map below illustrates darker colors as higher representative powers and shows the exact values for a congressional district when you hover over it.

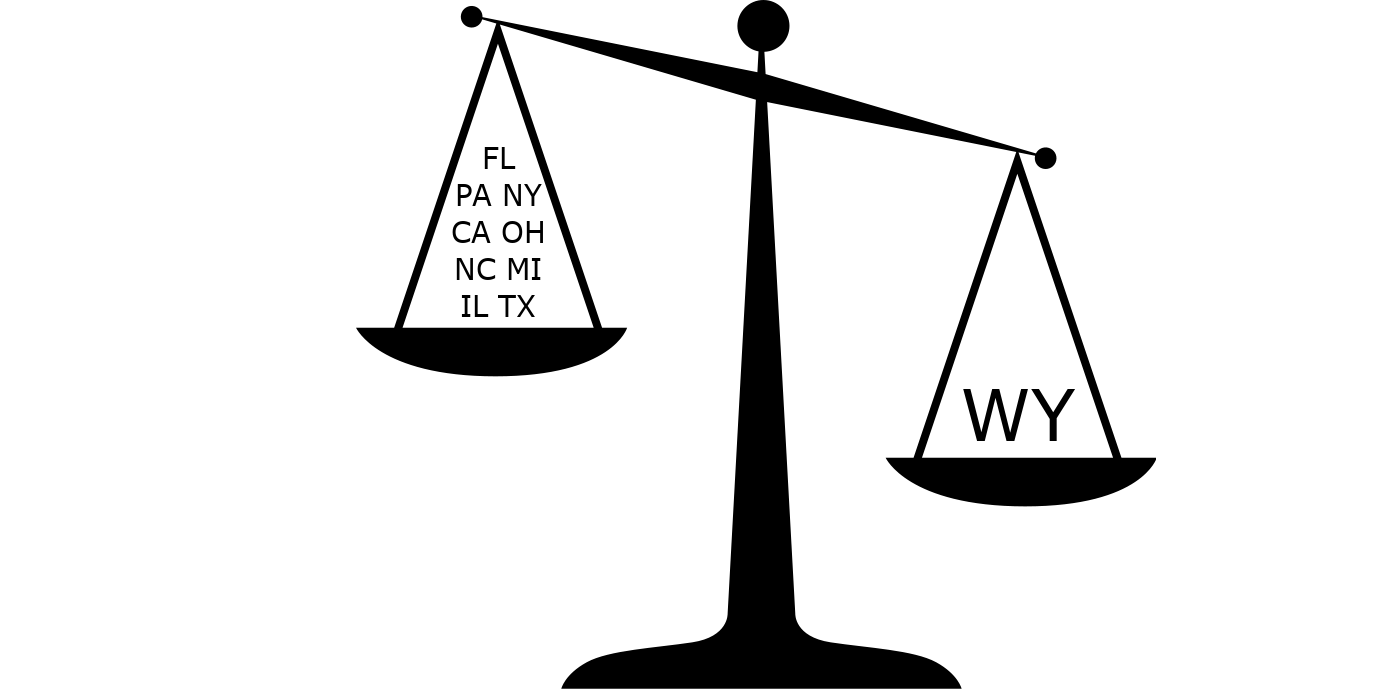

Taking a look at the two extremes, we can see a pretty shocking disparity in representation. A voter in Wyoming has more representative power than a Floridian, a Pennsylvanian, a New Yorker, a Californian, an Ohioan, a North Carolinian, a Michigander, an Illinoisan, and a Texan combined. This is purely due to the fact that while each of these five states are represented by two senators, only 200,000 voters pick those two people in Wyoming while multiple millions of voters pick them in each of the other four states. Using state-by-state voter demographics, we can expand the scope of our power metric to compare the average representative power of different demographics to see if any group in particular benefits from this arrangement. Comparisons based on sex and age show fairly similar representation between different groups, but race, political affiliation, and urban/rural delineation produce very unbalanced playing fields. As seen in the tables below, white voters have about 10% more representative power than non-white voters, Republican voters have 29% more than Democratic voters, and rural voters (based on CityLab’s classification) have 39% more than urban voters. This is again due to the disparate proportioning of representatives in the Senate and highlights the inherent representative inequity in our country’s democracy.

Representative Power By Race in 2016 (microreps)

| Race | House Power | Senate Power | Total Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 3.36 | 0.79 | 6.81 |

| Black | 3.40 | 0.66 | 6.26 |

| Asian | 3.63 | 0.72 | 6.77 |

| Hispanic | 3.61 | 0.50 | 5.79 |

Representative Power By Political Party in 2016 (microreps)

| Party | House Power | Senate Power | Total Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | 3.85 | 1.00 | 8.19 |

| Democratic | 3.16 | 0.73 | 6.33 |

| Other | 0.00 | 0.43 | 1.88 |

Representative Power By Urban, Suburban, and Rural Classification in 2016 (microreps)

| Party | House Power | Senate Power | Total Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | 3.29 | 1.18 | 8.42 |

| Suburban | 3.26 | 0.69 | 6.25 |

| Urban | 3.90 | 0.49 | 6.05 |

On a macroscopic scale, this leads to representation that is disproportionate to the actual populations they represent. Look at the percentages of elected congressional representatives in each party compared to the number of voters who actually voted for that party shown in the first figure below. Wins and votes in the House of Representatives have generally been proportional because the number of representatives is allocated based on population – until 2010 that is when congressional districts were conveniently redrawn by state governments. Can we talk about 2012 please? Democrats received more votes in aggregate during that election and only received 45% of the delegates. The equivalent graph applied to the Senate is even worse. For each year, we can add up the vote totals for each senator’s most recent election (e.g. for 2016, a senator elected in 2014 would contribute their 2014 vote totals) and again compare votes by party to wins by party. As you can see in the second figure, the relationship between these two values is loose at best. Since 2004, the percentage of votes cast for Republican candidates has never exceeded that of Democratic candidates, and yet, four of the seven congresses have had as many or more Republican Senators as Democratic Senators. That doesn’t exactly seem fair to me…

So what does this imbalance of representative power lead to? Unpopular ideas becoming law and popular ideas getting ignored. Despite being very unpopular amongst the general public, the attempted “skinny repeal” of Obamacare in 2017 almost passed in the Senate with votes from Senators representing only 39.8% of American voters, and it would have, were it not for the dramatic thumbs down of the late Senator John McCain. What did become law was the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, another unpopular bill which only needed the votes from Senators representing 40.2% of the electorate. The Supreme Court confirmations of both Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh were pushed through by Senators elected by less than 42% of the electorate. Even ignoring actual politics, it’s counterintuitive that such a diverse country would elect congress after congress of old white dudes rather than the melting pot that America so eagerly describes itself as.

So why does this happen and what can we do to fix it? Low voter turnout is a big factor that tends to benefit conservative candidates, which possibly explains why Republicans have received disproportionately higher representation since 2010. The 2018 midterms did show a huge surge in turnout but I can’t help but wonder if this is purely a reaction to outrage against President Trump that will quickly fade in future elections. Voter suppression continues to rear its ugly head, though often masquerading as concerns for “voter fraud”. Encouraging those around us to get involved in democracy and protecting the voting rights of every American citizen will help to align the voices of power with the voice of the people. But the more data-centric problem I want to address is gerrymandering and the restructuring of Congress. The exact geometry of congressional districts is a very complicated issue, so I won’t get into that level of detail here (though a future post might), but there might be a simpler solution. For those of you who think I’m trying to rewrite the Constitution, take a chill pill, this is just a thought experiment.

Let’s imagine a scenario where no districts are drawn. In this scenario, everyone still gets two Senators and the same amount of representatives in the House as before, but rather than voting in individual races, each person votes for a particular party (obviously this is problematic since people’s views don’t always align with any single party, but bear with me). Representatives and Senators are then divvied out to each party relative to the votes for each party. As you can see in the first two figures below, this setup compensates for most of the mismatch between votes and representation in the House, but the Senate remains inequitable. At least now the number of Senators for each party is proportional to the vote share, but Republican votes still go much further than Democratic ones. In fact, after trying a few different iterations of this model, the only version that produces a Senate that somewhat accurately represents the votes of the people (as seen in the third figure below) is when Senators are reapportioned based on census populations, the number of Senators is increased to 150, and people again vote for a party instead of a candidate. Crazy how far you need to go just to produce a level playing field…

I realize that the founding fathers established our government this way for a reason, that the Connecticut Compromise was necessary to get smaller states to ratify the Constitution, and that, like the Electoral College, it helps to guard against the tyranny of the majority. But right now, it feels a hell of a lot like we’re at risk of the opposite. A congressional majority elected by a minority of Americans is enabling an unpopular president (also elected by a minority of Americans) to enact legislation opposed by a majority of Americans. The framers were very intentional in their preambular word choice of forming a more perfect union, implying a good start but plenty of room to improve. Maybe it’s time to start thinking about making Congress a bit more perfect in terms of representation.